Non-Western nations have accelerated efforts to shape Africa’s information landscape, using a mix of overt media outreach, local partnerships, covert online operations, and targeted cyber activity to expand geopolitical leverage, promote strategic partnerships, and counter Western informational dominance. Russia, China, and Iran remain the most active operators, while the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey, and Saudi Arabia are rising contributors, each embedding influence efforts within broader economic, diplomatic, and security engagements. Narratives often emphasize anti-colonial sovereignty, South-South solidarity, and ‘development without conditionality,’ aiming to steer public opinion and decision-making. Together, these activities reveal a shifting contest for narrative dominance and ideological influence across the continent.

Russia’s influence on Africa

Following the invasion of Ukraine, Russia reconfigured its Africa strategy, replacing Wagner Group’s fragmented media networks with the Africa Initiative in September 2023, which combines a digital ‘press agency’ with local non-governmental organizations. The initiative distributes pro-Russian narratives across Burkina Faso, Niger, and other countries, promoting themes of sovereignty and resistance to Western interference. Similarly, the ‘Africa Corps’ assumed the Wagner Group’s military and political functions. Africa Initiative channels promoted the Africa Corps as a stabilizing force for Sahel juntas, enabling it to expand into countries like Equatorial Guinea by late 2024, suggesting intent to influence political narratives ahead of key electoral milestones.

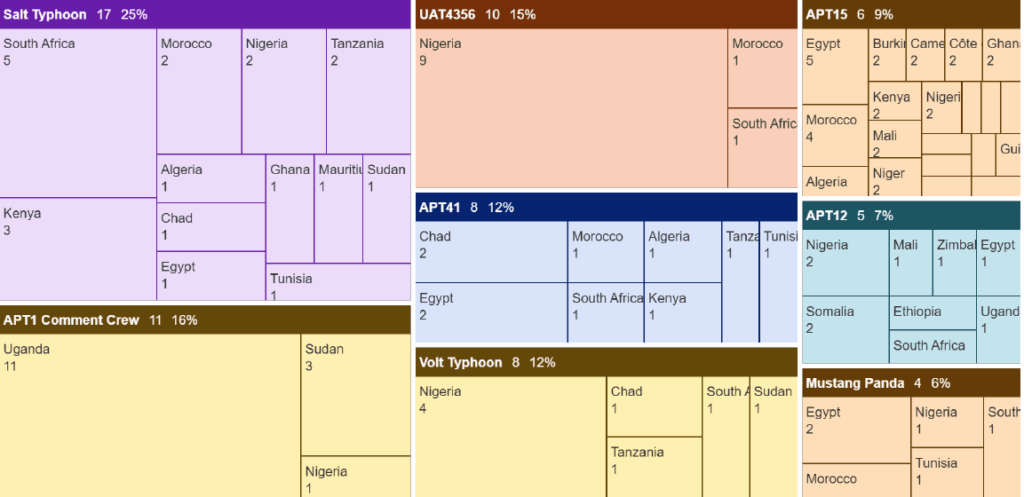

Russia has also intensified its election-related interference, with disinformation campaigns observed in at least 18 African countries since 2023 aiming to undermine electoral legitimacy and influence candidate perceptions. In early 2025, the UK’s deputy United Nations ambassador James Kariuki claimed that Russian-directed proxies have been planning interference operations in the Central African Republic, including disinformation campaigns and the suppression of political voices, to interfere with political debate amidst the upcoming December 2025 general election. Furthermore, Russia reportedly expanded its covert digital presence with ‘AI-Freak’ through 2024 and 2025, an Africa Initiative-linked network using fictitious news outlets, artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled avatars, and private-blog infrastructure to promote pro-Russia messaging. These efforts have been reinforced by cyber operations, with APT28 launching cyber campaigns in 2025 in an attempt to compromise African government accounts, enabling credential theft, internal surveillance, and intelligence gathering. African telecommunications, higher education, and manufacturing sectors were also notably targeted by Static Tundra, who exploited vulnerabilities in unpatched ‘End-of-Life’ Cisco networking devices to enable its long-term and ongoing intelligence gathering operations.

China’s influence on Africa

China’s influence employs a dual approach that combines extensive state media collaboration with covert digital operations and expanded surveillance infrastructure under the Digital Silk Road. Since 2020, digital outlets such as CGTN Africa and Xinhua have strengthened partnerships with African broadcasters, including Cameroon’s Afrique Média TV and Benin’s Etélé, which routinely air pro-China, and sometimes, pro-Russia narratives. These efforts build on the China Media Group’s Africa Link Union, designed to reinforce China-aligned messaging and reduce reliance on Western media. Digital infrastructure deployments, including Huawei’s ‘Safe City,’ raise concerns about potential misuse for social media monitoring and other surveillance capabilities, though governments deny such allegations.

Covert influence campaigns have similarly escalated. In 2024, Meta removed ‘Operation K,’ a China-origin coordinated network that attempted to infiltrate African online spaces using AI-modified visuals and the impersonation of Sikh diaspora figures to influence Nigerian discourse. Concurrently, China-aligned cyber operations have expanded, with GALLIUM attempting to maintain access to African telecommunications and defense networks in 2024 and 2025, and APT41 targeting a government IT provider in 2025 to exfiltrate sensitive data. Phantom Taurus, a recently discovered China-nexus APT, has similarly targeted African government and related service providers for over two years, with the group displaying significant interest in diplomatic communications, defense-related intelligence and critical government ministry operations.

Iran’s influence across Africa

Iran combines state media, proxy networks, and cyber operations with targeted diplomatic initiatives to expand its influence across Africa. State media outlets like PressTV and Al-Alam, and proxy channels, push anti-West narratives into Arabic-speaking Africa, with activity sharply increasing since the Gaza war, aligning with Iran’s efforts to expand political ties and secure influence in the Red Sea corridor. Extensive religious, cultural, and educational networks are further maintained across over 30 African countries, enabling Iran to distribute messaging that strengthens relationships with sympathetic elites while challenging Western competitors.

Meanwhile, some of Iran’s most active APT groups have targeted financial, government, energy, and telecommunication entities across Africa, signaling Iran’s intent to collect intelligence on key targets. For example, MuddyWater was observed deploying the Phoenix backdoor against North African organizations within the energy sector beginning August 2025, providing the group strategic and persistent access for intelligence gathering and potential disruption efforts. Meanwhile, leaked documents obtained from Amnban, a front company used by APT39, revealed orchestrated attacks targeting Royal Jordanian, Rwanda Air, Kenya Airways, and more, to facilitate the surveillance of perceived dissidents. Iran’s engagement in Africa forms part of a wider strategic effort to evade sanctions, secure resources, and cultivate political alliances, with reports in 2024 indicating the transfer of drones to the Sudanese Armed Forces, demonstrating Iran’s efforts to secure military footholds and counter Gulf rivals.

Other participating countries with influence in Africa

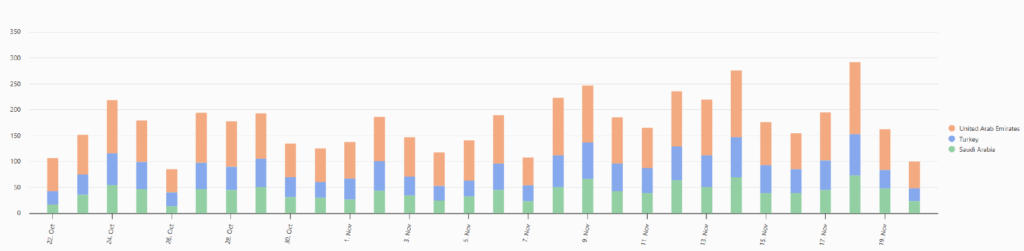

Turkey’s Africa strategy is primarily overt, with the state outlets TRT World, TRT Afrika, and TRT Somali broadcasting in multiple regional languages to present Turkey as a reliable alternative to Western and Chinese narratives. Initiatives like the Türkiye-Africa Media Forum further positions Turkish media engagement as a tool for shaping global narratives and countering Western ‘disinformation,’ reinforcing Turkey’s soft-power ambitions. Some cyber-related threats have been observed in connection with Turkey, including campaigns orchestrated by Stealth Falcon, an APT group suspected of having links with the UAE. Discoveries in March 2025 found Stealth Falcon targeting government and defense entities in Egypt for espionage intentions.

Saudi Arabia and the UAE similarly employ pan-Arab satellite networks, diplomatic summits, and targeted Arabic-language coverage to project influence and present themselves as attractive security and development partners. Their narratives often converge during crises, notably Sudan’s civil war, where competing information flows have depicted the conflict as a contest shaped by foreign sponsorship. Reporting indicates the Rapid Support Forces received advanced weapons sourced through UAE-linked channels, while the Sudanese army has obtained drones from Turkey and Iran. Such relations establish a proxy dynamic across the Sahel and Red Sea, shaping public opinion, legitimizing allied factions, and influencing regional and international interpretation of political transitions and armed conflicts.

Closing takeaways: influence, cyber operations, and geopolitics in Africa

Non-Western actors’ information operations have heightened the complexity of Africa’s media and political environment, blending soft-power narratives with covert cyber activity and targeted political influence. Such campaigns have the potential to shift public opinion, distort electoral discourse, and deepen conflict dynamics. To address such activity, some African states have strengthened partnerships with Western allies and civil society or technology platforms, while others have pursued ad hoc suspensions of foreign media during crises to limit information manipulation. Increases in influence activity is expected across Africa as external powers continue to compete for military access, resources, and diplomatic alignment, with advances in AI and inexpensive cyber capabilities lowering barriers for manipulation efforts and expanding the reach of foreign influence.

To learn how the Silobreaker Intelligence Platform can deliver insights to help you stay ahead of the latest geopolitical risks – specific to your organisation, request a demo today.